|

By Creezy Courtoy, Olfaction Training Expert The olfactory sense is the first sense to be developed in the foetus.

It starts during week 7. It is also the sense that arrives at maturity before the others during week 25. Immersed in amniotic liquid, the foetus swims in a bath of emanations and swallows four to five quarts of flavoured water per day. Before their first feeding, newborns show attraction for their own amniotic liquid and keeps this preference for the one or two days required to adapt to the new food source.. Strongly flavoured foods, such as cumin, ginger, anise, when consumed by pregnant women can contribute to an interesting prenatal olfactory experience for the child. The olfactory sense presents an important development in infant behaviour. The first odour discerned by newborns is the smell of their mother, and it is that smell which will determine their behaviour towards others. The mother not only shares genes with her child, but also shares phenotypic features that are smells. The olfactory sense of newborns is certainly their most developed sense. It guides the child, and the messages they receive make them feel secure. Only a few days after their birth, babies begin using their noses to receive all emanations passing around them. Their smell is so sharp that they encounter all odours, smells that we are not able to smell anymore. Their olfactory sense is so much more sensitive than that of an adult. Even though they do not yet know how to express themselves verbally to communicate their senses, newborns react to odours through motor reactions of the respiratory or cardiac rhythm changes. Babies less than two weeks old orient themselves automatically towards maternal odours. They will learn to recognize their mother by her smell, which they will prefer to any other smell and will bond with it; this process gives them the security they need to live. It could be said that newborns “see” with their noses. When they grow older, children will use their sight as their primary sense and the olfactory sense appears last. This is why it is important to preserve their olfactory sense, encouraging them to smell as often possible. This will prevent them to lose this important sense and feel insecure in the future. “Les Ateliers des Petits Nez” (Workshops for Little Noses) pilot project proposes olfactory menus to nurseries and kindergartens. With the support and the involvement of master chefs, IPF proposed the food needs of the child and to the development of their olfactory perceptions. Menus should comply with local dietary directives and also budgetary and organisational instructions. Menus are composed such in a way, not to mix ingredients. They can be ground, but only ground separately to not mingle fragrances, allowing children to discover them one by one. Chefs are different for each country, so in order to respect the children’s food culture, in our course we don't give you recipes but we will list the ailments adapted to baby and child development. It has been proven scientifically that the sense of taste is 85% olfactory. This training will not only preserve and awaken children’s olfactory sense, but also their tasting curiosity and a good food habit. Children will then learn from the youngest age to associate all of their senses together starting from the olfactory sense. More info about the course

0 Comments

An Interview by Creezy Courtoy, World Perfume Historian and Anthropologist The IPF Natural Perfumery Teacher's Academy is dedicated to accomplishing two vital goals: firstly, to educate enthusiasts on the art and science of natural perfumery, enabling them to transform their passion into sustainable careers; and secondly, to ensure the rich heritage of perfumery is preserved and passed on to future generations. Understanding the World Perfume History is crucial for any perfumer, not only to enrich their creations with inspired narratives but also to uphold and share this invaluable legacy. Now, let's introduce you to Vivian Trinh. Join us as we delve into her story. 1. Could you introduce yourself, including where you reside and your current occupation or activities? I am Viviane Trinh, an international independent perfumer and scent educator. I'm currently based in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam after years of training and working globally. My company's main focus is private R&D services, consultancy and tailored training programs for individuals and entrepreneurs. Settling down in a city that's not my homeland, with almost an opposite lifestyle compared to Hanoi - Where I was born - is a decision that requires a lot of my nerve! There are more and more people doing this, but it was definitely not something common back then! I was formally trained in Grasse focusing on the art and technique of raw materials and fragrance creation. But it was not enough to become a professional perfumer. I never stop there. For the last decade, I've been doing training and researching work with top perfumers and companies all around the world to collaborate and refine my skill. 2. Could you share why you chose to study History, particularly what inspired you? Was it a desire to learn more about the history of perfume in your region? I believe everything has a beginning. In order to master an art form, you have to truly understand it from the root. I never hate the fact that I'm almost obsessed with learning new skills and gaining new knowledge for my work as a perfumer. But funny enough, the more I try to move forward with the intention to "change", the more I realize that I'm getting back to the point where everything starts. Lots of the inspiration of our modern fragrances, including the raw material, the formula composition, the packaging or even the branding and marketing is actually nothing new but a more 'dressed up' and creative version of something that has already been done from centuries ago. Just like how we all fall in love with that homemade, fragrant herbal bath from our childhood before Chanel No.5, Shalimar and Mitsouko. Those little small scented moments are exactly the reason why I have had such a big love for perfumery since a very young age. Sometimes, I feel like no matter how much I've gained during this journey, I'm still that little girl who immersed herself in that afternoon bath, thinking about how she could get that vintage botanical dictionary from that local no-name bookstore. 3. What is the current state of natural perfumery in your country? What about its heritage? Do people still retain knowledge of their ancestral heritage? Despite the fact that our country has a rich tradition of using fragrant herbs not just for the purpose of beauty but also for medicinal and the spiritual purposes, I still find the urgent need to maintain the heritage worth considering. It's a bit painful to watch people shutting down their own garden or skipping on preparing natural scented products like tea, herbal bath, traditional medicine recipe, incense etc. because they don't have time or energy. The modern momentum of lifestyle is a challenge for people who still want to commit using the knowledge of their ancestral heritage. 4. Was the history course effective in reacquainting your country with its heritage related to perfumery? Education and creative ways of using scent is crucial to keep the heritage alive. I got all of that from the course. After joining the history program, I have a deeper understanding of not just my country's heritage related to scent, but also of a more comprehensive view about the world history of perfumery. The course gave me new knowledge about many practices that I thought I already knew by heart. It was truly a meaningful experience of reacquainting myself with my country heritage related to perfumery in a totally different way; but much more academic and professional! 5. Did you find it beneficial and necessary to take the global Perfume History Course? How did it impact you personally, and what changes have you experienced in your life as a result of this course and its certification by the International Perfume Foundation.

The course gives me extra courage to bring lots of my ideas from a shy scratch to a real product that I can proudly show my clients from time to time. That's priceless. If not to say, one of my career's bliss. It's been a very helpful course for me and it did help me so much with my career. I cannot tell you how much it helps me in my perfumery work. I'm looking forward to learning more from you and your courses in the future! I hold your certification in the highest place of my lab! I have to say that Creezy Courtoy's mentorship during the course was something out of this world. She employed incredible expertise in her teaching. But more than that, Creezy's heart-warming personality and her life-long passion for the art of perfumery was truly the biggest source of motivation for her students! My last word is: A special job requires a special mentor, and choosing Creezy's course was a game changing decision for my career. I cannot tell you enough how grateful I am. The Turbulent Journey of French Perfumery Through History By Creezy Courtoy World History Perfumery Expert and Teacher Throughout history, humanity's quest to bridge the divine and the earthly realms has often been mediated through the aromatic allure of perfumes and spices. However, this journey has not been without its dark epochs, notably during periods marked by the overwhelming influence of the Catholic Church, such as the Crusades, the medieval era, and the Inquisition. These were times when the Church's supremacy overshadowed even that of monarchs, intertwining religious power with the governance of states, culminating in France's separation of Church and State only in 1905. Such dominance led to the suppression of perfumes for daily use, associating them with witchcraft or frivolous, forbidden indulgences. Despite these challenges, the evolution of perfumery, much like science, experienced moments of pause rather than a complete halt. Innovative and pragmatic individuals emerged, defying the restrictions to maintain the therapeutic application of perfumes, utilizing flowers, plants, essential oils, aromatic vinegars, and "miraculous waters." Fortunately, these periods of constraint were interspersed with eras of abundance under monarchies that valued luxury and opulence over the Church's austerity. The dominion of the Church also impeded the broader progression of the sciences, holding the Bible as the singular path to salvation and often placing it in conflict with reason. Yet within the confines of monasteries, a different story unfolded. Monks became the custodians of ancient knowledge, cultivating medicinal plants and translating the works of Galen, Aristotle, Dioscorides, and Pliny. They preserved the beauty secrets and remedies of Greek and Roman antiquity, enriching them with the synthesis of translated Arabic manuscripts. Some of these recipes bordered on the magical, using ingredients and methods dictated by the movements of celestial bodies. The School of Salerno, a beacon of medical education in the 12th century, stood out for its quality of teaching and its secular approach, contrasting with the religious orthodoxy of most Western universities of the time. It honored both Greek and Arabic medical traditions, emphasizing the balance of the body's four humors as the foundation of health. The introduction of distilled alcohol for its revitalizing properties by figures like Raymond Lulle and Arnaud de Villeneuve marked a significant advancement in pharmacy, incorporating distillation into the preparation of remedies and cosmetics.

As perfumers ascended the social ladder, the first universities in Paris, Montpellier, and Padua were established, laying the groundwork for a more structured and secular education system. However, the contrast between the ideals of Salerno and the grim realities of the "Hotels-Dieu" in the West, which were far from the medical sophistication of Arabian hospitals, highlighted the stark differences in healthcare and hygiene practices between the cultures. This journey through the history of perfumery reveals not only the enduring human fascination with fragrance but also the complex interplay between religion, science, medicine and art. It underscores the resilience of perfumery as an art form, persistently evolving and flourishing despite the shadows cast by periods of suppression and ignorance. By Terry Johnson, IPF Vice Chair, Business and Marketing Expert Teacher During 30 years as a marketing consultant, one of the most common mistakes I have seen businesses make has been failing to properly prepare for, attend, and follow-up from an awards or other event.

Yet natural essence events, such as the New Luxury Awards, Perfumery Congress or International Natural Perfumery Summit represent profitable opportunities to network, gain industry insights, and showcase yourself, your company, and your brand. For Natural Perfumers or Natural Perfumery Brands, proper event marketing management starts with the decision to attend. Ask yourself: Does the event have the potential to improve my brand? Can my attendance lead to greater and more profitable sales? Managing attendance at events properly allows you to reach these and other important goals. Remember, we are in the Natural Essence High-Value Market, where higher prices can be achieved by offering consumers more value. Event attendance demonstrates industry leadership, which has great value to customers looking for companies, people, and brands they can trust and have confidence in. Additionally, being nominated for or winning an award has tremendous consumer value to a perfume brand. Here are several steps you can take to boost your profits from participation at an event: Pre-event Planning for Success

Event Participation

Profitable Post-Event Strategies Post-event follow-up is the most important part of event attendance, but it is also the least understood by most attendees. Many returning to work after an event fail to find the time to adequately follow up as they should for such a high marketing priority.

By Creezy Courtoy, IPF Chair The Devil is in Details*

Perfume, a symbol of luxury and elegance, captures our senses and evokes emotions like no other product can. In the world of perfumery, where every detail matters, it can be challenging to navigate the intricacies of staying relevant and successful. As a French outsider, I bring a unique perspective to your brand, offering a fresh lens to evaluate your strategy and branding. In this article, I will delve into the significance of details in perfumery and extend a personal offer of a free 30-minute coaching session to help refine your approach. The Power of Details In the realm of luxury goods, attention to detail sets apart the exceptional from the ordinary. Perfume, being an embodiment of luxury, demands meticulous craftsmanship and an unwavering commitment to excellence. Every aspect, from the carefully selected ingredients to the composition of the bottle, marketing and packaging, contributes to the overall experience and perception of the brand. The Role of Branding Branding plays a pivotal role in establishing a perfume's identity and resonating with its target audience. It encompasses various elements, such as the brand name, logo, packaging design, website, advertising campaigns, and even the emotions associated with the brand. A successful branding strategy should encapsulate the essence of the perfume, conveying its unique characteristics and values to consumers. The Value of an Outsider's Perspective Being an outsider to your brand, a teacher and a luxury expert, I bring a fresh and unbiased viewpoint. As a French individual born in a family in the perfume industry, I am intimately acquainted with the rich heritage and tradition of perfumery in my culture. This background allows me to offer insights and suggestions that may have been overlooked from within the industry. With a critical eye, I can evaluate your current strategy and branding, identifying areas of improvement and potential opportunities for growth. A Personal Offer: Free 30-Minute Coaching Session To demonstrate the value of my perspective, I extend a personal offer to you: a complimentary 30-minute coaching session. During this session, we can delve into your current strategy, brand positioning, and explore potential avenues for improvement. Together, we can analyze your target market, evaluate your competition, and discuss ways to enhance your brand's appeal and success. Perfume is a realm where attention to detail reigns supreme. To thrive in this industry, it is crucial to have a well-defined branding strategy that captivates consumers and sets your brand apart. As an outsider and a French individual, I offer a fresh perspective on your perfume brand, enabling us to examine your strategy and branding with a discerning eye. Don't miss this opportunity to gain valuable insights and refine your approach to achieve even greater success in the world of luxury perfumery. *"The devil is in the details." comes from a French expression: "Le dibble est dans les details". This expression conveys the idea that small, seemingly insignificant details can have a significant impact or cause unforeseen problems. By Creezy Courtoy, IPF Founder, Perfume Historian and Anthropologist Tracing the Historical Path of Incense, Myrrh and "Gold" As the essence of Christmas envelops us, the shimmering allure of gold intertwines with ancient trade routes and the symbolic journey of the Three Kings. Egypt's pursuit of incense, myrrh, and oud through the exchange of gold highlights the interconnectedness of cultures and the quest for precious treasures. Together, let us embrace the universal values of peace and unity, inspired by the story of the Three Kings, the timeless significance of gold in our celebrations and the spirit of peace. The Magnificence of Incense, Myrrh, and Oud During antiquity, Egypt was known for its rich trade connections and its desire for valuable commodities, including incense, myrrh, and agarwood. These aromatic substances held significant cultural and religious importance in ancient Egypt, and they were highly sought after for their fragrance and other perceived qualities. The fragrant smoke of incense was believed to carry prayers and offerings to the heavens. Myrrh, used in embalming and as a sacred offering, symbolized purification and spiritual connection. Oud, with its captivating aroma, was a prized ingredient in perfumery and incense-making. Egypt, renowned for its opulence and reverence for these aromatic substances, sought to obtain them from regions along the Perfume Roads. Incense: Incense was widely used in religious rituals, offerings, and ceremonies in ancient Egypt. It was believed to possess purifying and protective properties, and its fragrant smoke was thought to carry prayers and offerings to the gods. To obtain these sought-after varieties, Egypt had to engage in trade with regions like Arabia and the Horn of Africa, where these substances were produced. Myrrh: Myrrh, another aromatic resin, held religious and medicinal significance in ancient Egypt. It was used in embalming practices and as an offering to deities. Egypt's access to myrrh was limited, as it primarily came from regions like present-day Somalia, Ethiopia, and Yemen. Agarwood (Oudh): Agarwood, also known as oudh, is a fragrant wood derived from the Aquilaria tree. It has a rich, woody aroma and is highly valued in perfumery and incense-making. Agarwood was sourced from regions such as Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Egypt's Trade: Gold for Precious Fragrances The acquisition of these precious substances, however, often required the exchange of large quantities of gold due to their scarcity and demand. Gold, which was highly valued, served as a medium of exchange in international trade. As caravans traversed desert landscapes, laden with gold, they ventured towards regions like Arabia, the Horn of Africa, and the Indian subcontinent. Egypt's desire for incense, myrrh, and oud drove the trade of this precious metal, forging connections and fostering cultural exchange along the ancient trade routes. Gold mining, both in Egypt and through trade with neighboring regions, was a significant source of wealth for the ancient Egyptians. Egypt's abundance of gold during antiquity can be attributed to several factors, including its geographical location, natural resources, and historical developments. Egypt had its own gold deposits, primarily located in the Eastern Desert, near the Red Sea. Ancient Egyptians developed mining techniques to extract gold from these deposits. They employed methods such as panning, sluicing, and tunneling to access the gold-bearing ore. Egypt's location in northeastern Africa placed it in proximity to gold-rich regions, such as Nubia (present-day Sudan) and the Eastern Desert. Nubia, located to the south of Egypt, was particularly renowned for its gold mines. The Nubian region had significant gold deposits, including alluvial gold found in riverbeds and veins of gold embedded in rocks. Gold held immense economic value in ancient Egypt. It was widely used as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a symbol of wealth. Gold was employed for various purposes, including trade, religious offerings, ornamental and luxury items, and the adornment of pharaohs and temples. The demand for gold, both domestically and internationally, contributed to its importance as a form of wealth for Egypt. Additionally, Egypt was able to acquire gold as tribute or payment from conquered territories or through diplomatic relations with neighboring regions. Gold held deep cultural and religious significance for the ancient Egyptians. It was associated with the sun god Ra and was considered a symbol of divine power and eternal life. Gold was used in religious rituals, temple construction, and burial practices, indicating its importance beyond its economic value. These factors combined to make Egypt a significant center for gold acquisition and accumulation during antiquity. Egypt's control over gold mining, its trade connections, and its cultural reverence for gold allowed it to amass substantial wealth in the form of this precious metal. The Journey of the Three Kings The Three Kings are believed to have originated from different regions of the ancient world. Melchior, often depicted as an elderly Persian scholar, hailed from Persia (modern-day Iran). Balthazar, portrayed as an African or Arabian nobleman, is thought to have come from Sheba or Arabia Felix (present-day Yemen). Lastly, Gaspar, a youthful figure, was said to have hailed from Saba (modern-day Ethiopia or Sudan). The Three Kings carried precious gifts symbolizing their reverence and respect for the newborn baby. These gifts were not only symbolic but held great value during the time. Beyond their biblical narrative, the journey of the Three Kings holds historical significance. It reflects the ancient trade routes that connected civilizations, the cultural exchanges that took place, and the role of Arabia as a center of commerce and knowledge. The gifts the Kings presented also highlight the importance of incense, myrrh, and gold in ancient societies. To reach their destination, the Three Kings embarked on a perilous journey across the vast Arabian Desert. This desert, with its shifting sands and treacherous terrain, presented numerous challenges. The exact route they took remains a subject of speculation, but historical evidence suggests they likely followed ancient trade routes and oasis trails, navigating by the stars and their knowledge of the desert. The Path through the Arabian Desert

From Persia to Arabia: Melchior, the Persian king, set out from his homeland, traversing arid plains and rugged mountains. His journey took him through the ancient cities of Persis, Parthia, and the Arabian Peninsula, eventually leading him towards the southern Arabian region. Melchior presented gold, representing kingship and wealth. From Saba to Arabia Felix: Balthazar, originating from the Kingdom of Saba, embarked on his expedition from the southwestern Arabian Peninsula. He embarked on a challenging trek through the deserts of Yemen, navigating the arid landscapes and ancient trade routes that connected the region with the rest of the world. Balthazar offered frankincense, a fragrant resin used in religious rituals, symbolizing divinity. From Saba to the Land of the Nile: Gaspar, the youngest of the Three Kings, hailed from the Kingdom of Saba. He embarked on his journey, traveling northward, along the Red Sea coast. Crossing vast stretches of desert, he eventually reached the ancient land of the Nile, making his way to the heart of Egypt. Gaspar bestowed myrrh, an aromatic resin used in embalming, symbolizing mortality and sacrifice. Gold or Liquid Gold? While Melchior is traditionally associated with offering gold, it is intriguing to explore the symbolic connection between gold and oudh or agarwood, the most precious scent in Arabia, often referred to as "liquid gold." Gold has long been associated with wealth, luxury, and kingship in various cultures. In the context of the Three Kings' story, Melchior's gift of gold symbolizes the recognition of the newborn baby's royal status and the acknowledgement of his future as a great ruler. In addition to its material value, gold also represents purity and divinity. Its shimmering brilliance has often been associated with the divine presence and elevated spiritual significance. Similarly, oudh or agarwood holds a special place in Arabian culture and has been treasured for centuries for its exquisite fragrance and rarity. Oudh is derived from the resinous heartwood of the agar tree, primarily found in Southeast Asia, India, and the Arabian Peninsula. It is a highly sought-after fragrance ingredient, renowned for its rich, complex aroma, often described as woody, balsamic, and captivating. The extraction process of oudh is meticulous and time-consuming, contributing to its high value. The term "gold" used to describe oudh or agarwood in the context of the Three Kings' gifts signifies its extraordinary worth and significance. Oudh is considered a precious treasure, a symbolic representation of luxury, spirituality, and devotion. Just as gold is associated with kingship, oudh is associated with nobility and opulence in Arabian culture. It is important to note that while the inclusion of oudh as "gold" in the Three Kings' story may have cultural significance and symbolism, it is not a historical fact but rather a poetic interpretation that enriches the narrative and adds to its allure. The inclusion of oudh as a symbolic representation of gold in some interpretations of the story is a way to add cultural richness and depth to the narrative. It draws upon the significance of oudh in Arabian culture and its association with luxury and opulence. The Symbolic Journey of the Three Kings, a desire for peace, harmony: The biblical tale of the Three Kings, or Wise Men, embarking on a journey across the desert to present gifts to the infant Jesus in Jerusalem, encapsulates the spirit of peace and harmony among the three Abrahamic religions. Symbolizing Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Three Kings epitomize the unity and shared reverence for the divine. The gifts they brought signify not only material wealth but also spiritual devotion and the pursuit of peace. Their passage through the desert echoes the importance of pilgrimage and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. The exchange of these precious gifts symbolizes a desire for peace, harmony, and the recognition of the divine presence within humanity. By Creezy Courtoy, IPF Founder and Chair and Perfume Anthropologist Understanding Scent Preferences for Creating and Distributing Fragrances Distributing a perfume in several countries can be a real challenge. It can be just a failure for famous brands, but a dangerous game for small brands who can financially lose everything. In the art of fragrance creation, understanding the anthropology of perfume is essential. By delving into the diverse scent preferences shaped by culture, region, and individual sensitivities, fragrance creators can craft scents that resonate on a deeper level. The ability to influence others through the strategic use of preferred scents becomes more attainable when armed with the knowledge of anthropology of perfume. So, let's embrace the rich tapestry of scent preferences and create fragrances that captivate the senses and forge lasting connections. Men and women have long recognized the power of scents in influencing their fellow humans. While it is impossible to predict exactly how an individual will respond to a particular smell, psychologists have discovered intriguing connections between odors and memories. For example, a single floral scent can evoke memories of a crowded elevator, a funeral, an old boyfriend's excessive aftershave, or even the onset of hay fever. Despite the varying responses, scientific investigations have revealed common preferences among sexes, cultures, age groups, and personality types. By understanding these preferences, perfumers can safely select the countries where their products will be successful. Cultural Influences on Scent Preferences Cultures play a significant role in shaping scent preferences and the ways in which scents are used. Let's explore some fascinating examples: The Japanese: Perfuming Daily Life

In Japanese culture, scent has permeated almost every aspect of daily life. From personal care products to household items, the Japanese have cultivated a deep appreciation for fragrance. They even engage in games with friends and family that involve identifying various smells. Understanding the importance of scent in Japanese culture can provide valuable insights when creating fragrances for this audience. In contrast, the Anglo-Saxon approach to scent is more understated. Publicly smelling one's food or wine is considered uncouth in their culture. However, the bouquet of wine and the taste of food both heavily rely on the sense of smell. Anglo-Saxons prefer subtler scents when it comes to personal fragrance, avoiding being too "obvious." Respect for cultural norms is crucial when designing fragrances for this audience. Across different cultures, there are notable variations in scent preferences. For instance, Orientals appreciate heavy, spicy, and animalistic perfumes. Valerian root extract, which is detested by most Europeans, is favored in Oriental cultures. On the other hand, Asians may struggle to understand the Western love for pungent cheeses. Recognizing these cultural differences is essential for creating fragrances that resonate with specific target markets. Regional Influences on Fragrance Choices Apart from cultural influences, regional factors such as climate and environment also shape fragrance preferences. Northern Europeans, living in colder climates, often prefer heavier fragrances that provide warmth and comfort. In contrast, Mediterraneans are drawn to sophisticated floral scents, likely due to their love for being surrounded by flowers. Taking these climate-based preferences into account can enhance the effectiveness of fragrance creations. Universally Pleasant Smells and Aversions While there are cultural and regional variations, it is safe to say that there is a broad agreement within the human race about what smells pleasant and what doesn't. Most people appreciate flower and fruit scents, while being repulsed by foul odors such as rotten eggs, fish, or stagnant drains. Understanding these universally pleasant and unpleasant smells can guide fragrance creators in developing appealing and attractive scents. People's responses to scents can also vary based on their individual sensitivities, as well as the influence of education, societies, and marketing. Therefore, do not miss your opportunity to sell and distribute successfully your perfumes worldwide. Learn more about the Anthropology of Perfume and get ready for your perfume distribution. By Creezy Courtoy, Perfume Historian and Anthropologist For a long time, Perfume remained an important source of revenue for Greece. In the Bronze Age, Egypt, due to its geographical, protected and isolated location and by its geological wealth and cultures, was obliged to import raw materials from Arabia and the Aegean Islands. Egypt was rich in gold, but did not possess the raw materials necessary for making perfumes. Arabs, Hadramaout (South Yemen) and Dhofar (Oman) provided Egypt with scented woods and resins (myrrh, incense, olebanon) and Greeks provided flowers, herbs and their talents of perfumers in the confection of perfumed oils. Greece was then a country of farmers, breeders, Artisan Corporations and a fighting aristocracy. Greece was a country of scents, herbs, flowers and plants. Due to its geographical location and its numerous surrounding islands, Greece was a gateway to Asia Minor, Syria and Egypt. The Greeks are credited for having added to spices, to gums and to balms, oils scented with flowers. Flowers and plants used for export had to be preserved and transformed. Olive oil, one of the main resources of Greece, was used as an ointment and as an excipient or absorbent in perfume oils. The Greeks practiced ‘enfleurage’ and from an early age, the art of creating perfumed oils. In the time of Ancient Egypt, perfume was used mainly to communicate with the gods; during Ancient Greece, it was used to resemble the gods. Perfume was actually used by Egyptians but never throughout history could Egyptians, impregnated with fragrant scents, assist human divination, not only in the sculptural art that gave the gods their human faces and bodies, but also in the wearing of perfume that participated in this quest of perfection by making humans more divine. Since gods smell good, to be like them you must smell divinely good. The Greeks associate perfume to the erotic power of the union of two people. The Greeks buried their dead with their possessions and a terracotta vase or alabaster containing perfume. For poor people, vials painted onto the coffin replaced the alabasters. The perfume played the role of intermediary between the world of people and that of Gods and helped the dead to reach the other world. In everyday life, perfume was not a neutral thing, « thion », « myron » or a simple aroma but a feminine being. It was used in and for everything; as a life elixir, a nectar, and a ragweed. It gave hope of immortality to humans because the Gods were beautiful and immortal. For the author Virgil, Venus (Aphrodite) created the rose perfume. "One day, Venus wanted to cut a white flower and pricked herself, covering her with an everlasting purple color. To Cupid, the rose seemed so beautiful that he kissed it… This is where its smell comes from." Towards the end of the II Millennium BC, the Greek industry acquired knowledge, “art de vivre” and know-how that gave birth to the Europe of Perfumes. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History text (XIII 9-12 XV, 28-38), mentioned at least 22 kinds of perfumed oils, most of them extracted from plants naturally growing on the island of Crete: cypress, marjoram, broom, iris, spikenard, rose, myrtle, laurel, crocus, lily, juniper, pine, nut, almond, carnation, poppy, coriander, aniseed, cumin, narcissus, and daisy. During the period of the Mycenaeans, even taxes were paid in plants. Circa 1450 BC, perfumery was truly an industry controlled by the Masters of the Mycenaean palaces. The decryption of linear writing par par Alice Kober in 1947 and Michaël Ventris et John Chadwick in 1952, found on 20% of the 7000 Mycenaean clay tablets of the islands of the Aegean Sea show that a prominent position was given to scented products, ointments, incenses, aromatic wine, perfume oils, and spices. Everything listed on these tablets provided a real accounting of orders and exports. Perfumery, in Greece was mainly a branch of medical science. Some odors excited or inspired while others healed. Hippocrates studied skincare in a comprehensive manner and advocated perfumed baths and massages combined with the use of aromatic substances to treat some diseases. He recommended remedies based on sage, cinnamon or cumin, applied either through fumigation, potions, frictions or aromatic baths. He also used perfume as a protection against diseases. It is said that he saved Athens from the plague by burning aromatic woods and hanging flower garlands in the streets. Hippocrates considered various oils used to preserve odors, the use of flowers and spices and the choice of a hundred perfumes for different states of mind and health both for men and women. "Because both senses – taste and smell – are linked one to another, each serves somehow the pleasure of the other and man can thus discover fragrances either because it pleases the taste or the sense of smell.’’ Théophraste (400BC Book of Odors – Chapter III) The Greeks were the first to utilize ‘’packaging’’ and ‘’marketing techniques’’. The alabasters, the oenochoes and the ariballoi were all made of terracotta decorated with trendy themes, perfectly understood by all the populations of the Mediterranean and all refer to Greek mythology or to major known themes. These vials were presented in various sizes in the same way as bottles are today: from the small inexpensive ariballoi vial containing little perfume to the enormous and expensive ariballoi jar which would today correspond to 1 litre of perfume. For a long time, perfumery items remained an important source of revenues for Greece. Cargos of wax-sealed vials and vases containing perfume oils were continuously leaving Peloponnese or Crete towards Mediterranean ports. Masters in the Art of creating perfumes; Masters in the Art of Cosmetics, ornament and make-up; Masters of the Art of packaging: the Greeks created the first industry of perfumery during Ancient times. If you want to learn more about the Anthropology and History of Greece or any other countries, enrol for Creezy Courtoy's Courses or Master Classes

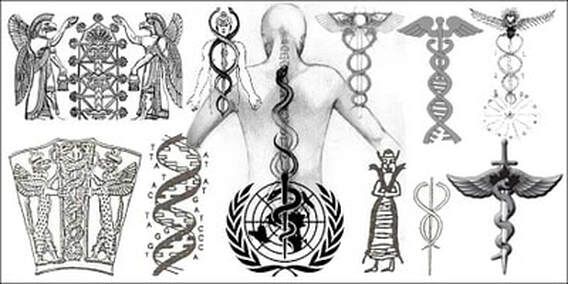

By Creezy Courtoy, World Perfume Historian and Anthropologist My first passion has always been the impressive history of perfume and I could never think the way I think today if I did not spend all my life collecting perfume antique artworks and searching for the true perfume history. When you start searching, it never ends and still today I am looking for something; each piece leading me to more research. In the Arab World, perfume was precious, it was considered as pure gold. Let me invite you to follow me on the history of perfume in that part of the world. Circa 4000 B.C., the Sumerians built the first City States such as Sumer, Ur, Uruk or Nippur, along rivers. “Mesopotamia” literally means “the country between the two rivers”. Located between Tiger and Euphrates, this region currently corresponds to Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Southern Turkey and Israel. Cuneiform writing carved onto the clay tablets reveals formulas and perfumes used by these ancient populations since the middle of the third millennium B.C. Lebanese cedar, cypress and myrtle were the three most used fragrances. Originally, the gods loved natural perfume and got close to those who wore them. This is why the servants of the temple covered their bodies with myrtle oils before carrying out the rituals and the offerings to the numerous gods. Perfumes were reserved to divinities, kings and temple worship. Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, lived a rather eventful life, characterized by his vain quest for immortality. Perfume, the most noble and precious element then made its way into his alchemy research. The relation between medicine and gods was very close. One of the healing gods was the two-headed snake Ningishzida. The snake, symbol of eternal life, might have been the first icon of caducei. His name in Sumerian is translated as “lord of the good tree”. About 1000 years later, the Akkadians replaced the Sumerians and created the first empire of the world ruled by Sargo the Ancient.

Phoenicians sailors and traders settled on the coast of Lebanon and build colonies in Cyprus, Crete, sicilia, malta and Northern Africa. Tyr, their capital, having enjoyed a permanent relation with Egypt and Mesopotamia, became one of the most important ports. Circa 1900 B.C., Babylonians replaced Akkadians. Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.), created the powerful empire of Babylon. Babylon remained the main warehouse of spices from all over the world for a long time. It received spices from India and from the Persian Gulf, scented gums from Arabia and balms from Judea. Nabuchodonosor I (1124 B.C.) had his palace built with cedar beams and cypress doors that smelled kilometers away. According to Herodotus, over 1000 talents of pure incense were burnt every year on the altar of Belus. Zoroaster prescribed the use of perfumes on altars five times a day. In the hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the Ancient World, all the scented plants were showcased. According to Diodorus, (Greek columnist of the 1st century, contemporary of Julius Caesar) cedar, mimosa, Arabian jasmine, lily, crocus, iris, violet and rose, gave the Kingdom the reputation of owning the most beautiful roses of the Ancient Orient. Chaldeans, circa 600 B.C., represented the last civilization of Mesopotamia with two famous Kings: Nabopolassar and Nabuchodonosor II. They inherited a great culture, developed astronomy, astrology and added all this science to the Art of Perfumery. Plants and resins must be collected at certain times in the day, or at a precise moment in the year in order to reinforce their efficiency. The fall of Babylon, conquered by the Persians in 539, did not upset the trade of perfumes. Focused on the fringes of the desert, the caravan kingdoms owed an important part of their prosperity to the trade of perfumes. Sidon (then Carthage) replaced Babylon as the capital of perfume and spices. For the Cananeans as well as for Babylonians, Phoenicians and Sabaeans, perfumes and spices were both pure gold and divine message. For thousands of years, they carefully preserved the trade and even caused wars. Arabia Felix, also called the “Fertile Crescent”, stretched from Oman to the Suez Gulf and across its length were paths taken by the caravans. Called “The Perfume Roads”, these ancient trails linked the south to the North of this continent and crossed the deserts of one of the oldest countries in the world. To ensure the security of the trade on The Perfume Roads, in the 10th century B.C., Balkis, the Queen of Sheba organized a meeting with Solomon, the Hebrew King... If, like me, you are impassioned by World Perfume History, I will be happy to transmit my knowledge to you and tell you more about the Perfume History in the Arab World. We definitely need more perfume history teachers to make sure the perfume heritage will be preserved and transmitted to the next generations. By Creezy Courtoy, Anthropologist and Olfaction Expert OUR CHILDREN OLFACTORY SENSE The Olfactory Sense is the First Sense to Begin Development in the Fetus I have always been fascinated by olfaction, which is why I spent time studying gorillas. Like gorillas that use 100% of their olfactory sense, newborns have the same powerful sense of olfaction. Olfaction is the most powerful sense of all their senses. It is the first sense to begin development in the fetus, and arrives at maturity before all the others. Immersed in amniotic liquid, the fetus swims in a bath of emanations and swallows four to five quarts of flavored water per day. Newborns See With Their Nose The first odor discerned by newborns is the smell of their mother, and it is that smell which will determine their behavior towards others. The olfactory sense of newborns is certainly their most developed sense. It guides the child, and the messages they receive make them feel secure. Only a few days after their birth, babies begin using their noses to receive all emanations passing around them. Their smell is so sharp that they encounter all odors, even those we are no longer able to smell. Their olfactory sense is more sensitive than that of an adult. Even though they do not yet know how to express themselves verbally to communicate their senses, newborns react to odors through motor reactions of the respiratory or cardiac rhythm changes. Babies less than two weeks old orient themselves automatically towards maternal odors. They are dependent on their mother's constant attention to feel psychologically well. They will learn to recognize their mother by her smell, which they will prefer to any other smell and will bond to it; this process gives them the security they need to live. This is why we can say ”newborns see with their nose”. The First Years of a Child's Life Are Very Critical.

The olfactory sense, (and instinctive sense, considered as too animal-like), was almost entirely rejected by our society. In our present adult environment sight prevails over all other senses. Human beings have lost their olfactory sense and must learn to smell again. Olfaction is a very important sense in the harmonization of human beings because to feel good, we need all of our senses to be in balance. If the olfactory sense is not maintained, it progressively disappears sometimes completely when approaching old age. It is only lately that our society is realising how important the sense of smell is. Still, many parents and educators do not pay much attention to their own sense of smell and are not teaching their children to do so. This is why, I have put in place a Children Olfactory Preservation Program starting at 4 months, when babies start eating solid food. The first years of a child's life are very critical. Children’s sensory experiences help them build a bundle of emotions and sensations that gives them tools to grow and develop in harmony. It is necessary to help babies and young children preserve their olfactory habits. How Can We Engage Kids To Preserve Their Olfactory Instincts in This Visual And Auditory Civilization? How can we recreate olfactory education and re-develop olfactory habits? Les Ateliers des Petits Nez (Workshops for Little Noses) have been especially created to teach babies and children how to preserve the power of their olfactory sense. The International Perfume Foundation previously tested this Children Olfactory Preservation Program in nurseries and kindergartens. Today I am giving lectures on this subject, and I have created an Online MasterClass to teach young parents, grandparents, educators, nurseries, kindergartens and schools to accelerate this movement. Our children are our future, they need to feel good and to feel secured to face the challenges of this changing world. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

- HOME

- ABOUT

- IPF CERTIFICATION

-

COURSES

-

MASTER CLASSES

- Teaching Methodology

- Natural Raw Material Extraction Methods >

- Natural Candle Making

- Healing Gardening

- Sustainable Oud MasterClass

- World Perfume History Master Class

- Scent Design and Formula Building >

- Fragrant Botany & Chemistry >

- Perfume Design, Concept and Storytelling

- French Natural Aromachology #1

- French Natural Aromachology #2

- Olfaction Training for Children

- Accords - Chypre

- Accords - White Florals 1

- Accords - Fougeres and Aromatics

- FRAGRANCE DEVELOPMENT

- SPEAKERS

- EXHIBITIONS

- Partners

- Blog

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed